The Railway: A Woman's World

At the start of the 20th century, 4,564 women were employed on Britain’s railways, representing less than 1% of the total workforce. In this male-dominated sphere of employment, where women did secure a position it was often in line with contemporary preconceptions of suitable roles. The exclusion of women in rail did not require any justification; a woman’s place was predefined by society, and the status quo went largely unchallenged. However the two world wars provided the circumstances and opportunities for women to enter industry previously determined as male only.

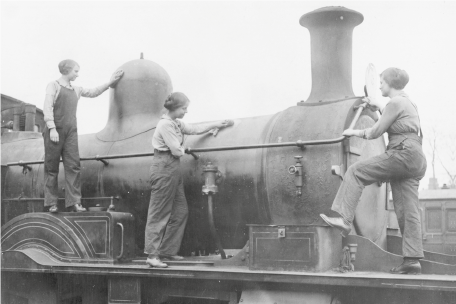

Railway companies were one of the first major employers to recruit women during the First World War, enabling some male workers to be released for the front. During this period, 55,942 women were employed in Britain’s railway companies, initially in roles such as clerical work or ticket collection before taking on increasingly physically demanding roles including as station porters or engine cleaners.

Images: ©IWM (left) / Image: ©John Alsop Collection (right)

Images: ©IWM (left) / Image: ©John Alsop Collection (right)

Female railway workers traded long skirts and corsets for men’s breeches during the First World war to carry out their new strenuous and dangerous roles. Before the war, it was almost unheard of for women to wear trousers in public.

Image: ©IWM

Image: ©IWM

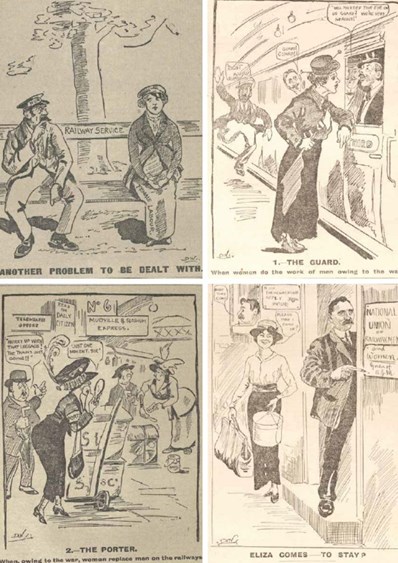

Although vital to keeping the railways running, women were considered a novelty and were often the subject of scepticism, if not outright hostility from their male colleagues.

Image: ©National Union of Railwaymen Archive, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

Women were often placed into roles without receiving basic training, with limited experience of the type of work expected and were subjected to discrimination - earning less than men for the same role. As a rule, a woman would be paid one-third to one-half the rate a man got. In 1869, the average weekly wage of a railwayman including boys and trainees was 26s 8d while women took home anything between 8s to 15s. The idea of women receiving the same pay as men would have been laughable. The logic was that women were not the family breadwinners and therefore did not have the need for money that men did

In addition to the pay gap, the excellent travel benefits that drew many working-class people to employment in the industry were consistently withheld from women. The Midland Railway Company, operating from St. Pancras was relatively progressive in its approach by establishing training facilities for female staff at St. Pancras and Somers Town Goods Stations.

Image: ©IWM

Image: ©IWM

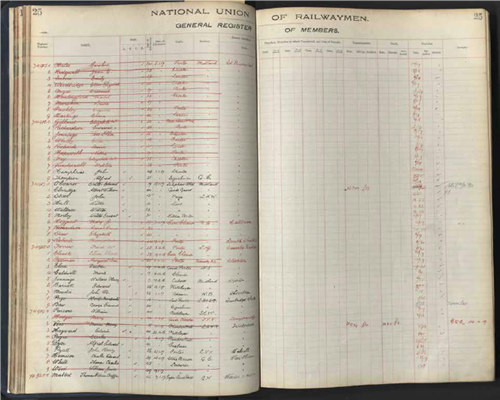

As women were employed as emergency temporary labour they were not initially permitted to join the railway trade unions. By 1915 they comprised such a high proportion of the workforce that their position could no longer be ignored and they were permitted to join the unions.

Once the unions began to take on female members they demanded equal pay to protect the wage rates for servicemen once they returned from the war. The women’s names were written in red ink in the NUR’s register of members to make it easier to identify who would later be struck off once they had finished war work.

Image: ©National Union of Railwaymen Archive, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

Railway companies made it abundantly clear to new female recruits that the jobs they had obtained were temporary and would need to be given up when the war was over. Women were also expected to resign upon marriage though in some salaried grades it was common that they would be dismissed immediately by their employer.

Although many women were thus forced out of their employment at the end of the First World War, a number continued to work and in the two decades that followed, approximately 26,000 women worked on Britain’s railways. Numbers increased again during the Second World War. Fewer restrictions were placed on the types of roles they were permitted to undertake as they filled positions such as passenger guards, engine cleaners and signallers.

Image: ©Cliff Rowe/ NRM

Unlike the First World War, the need for labour on the home front was so great that the government judged that more women would be needed in war work than they got from volunteers alone. This ushered in the National Service Act (No. 2) in 1941 which initiated national conscription of women. Originally, only single women were eligible but by mid-1943, almost 90% of single women and 80% of married women were employed in vital roles as part of the war effort. Women were called up for work in a range of industries with 105,000 women employed as part of the railway war effort

Image: ©Planet News/ Science & Society Picture Library

Although the Second World War did not see women in all roles, such as engine drivers due to the length of training required and union opposition, the Second World War saw women increasingly taking on a significant range of technical, manual and clerical duties.

Image: ©IWM

Mrs Molly Temperley, 26, does some essential signal maintenance (below), she is seen climbing up a signal post to fix a newly cleaned lamp, circa 1940 - 1943.

Image: ©Daily Herald Archive/ National Museum of Science & Media

Image: ©Daily Herald Archive/ National Museum of Science & Media

Decades later in 1978, the industry saw its first female train driver, Karen Harrison. This heralded a new age for women in the railways as it demonstrated that formal barriers had been broken down, although that didn’t mean it was easy. Harrison described her years as a train driver to be “ten years of hell, ten years of heaven” due to the lingering attitudes other railway workers and passengers held regarding women in conventionally male lines of work.

Today women today account for approximately one in five of the railway workforce. While the formal barriers of the 19th and 20th centuries have been consigned to history, there is an urgent need to encourage more women to consider a career in rail.

As shown, the wider St. Pancras team is proud of its diverse workforce and is leading the way in employing women in key roles. HS1 Ltd, where women represent over 50% of the senior management team, supports organisations such as Women in Rail that are helping to make this a reality across the industry.