The Creation of an Icon

In the space of 150 years St Pancras transformed from open fields and hamlets to dense urban development

In the late 18th and early 19th century St Pancras was still extensively rural in character and featured its own spa and pleasure grounds for those seeking respite from the city.

Image: ©Antiqua Print Gallery/ Alamy

Image: ©Antiqua Print Gallery/ Alamy

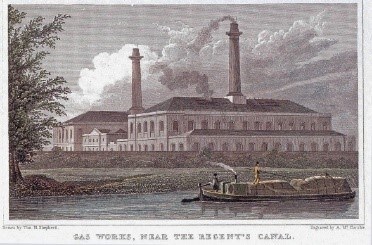

However, the relentless industrial progress of the time soon changed the landscape forever. First came the Regent’s Canal in 1820 bringing with it industry attracted to the transportation possibilities of the canal such as the Imperial Gas, Light and Coke Company which built the gasholders still visible next to the canal.

Image: ©London Canal Museum

Image: ©London Canal Museum

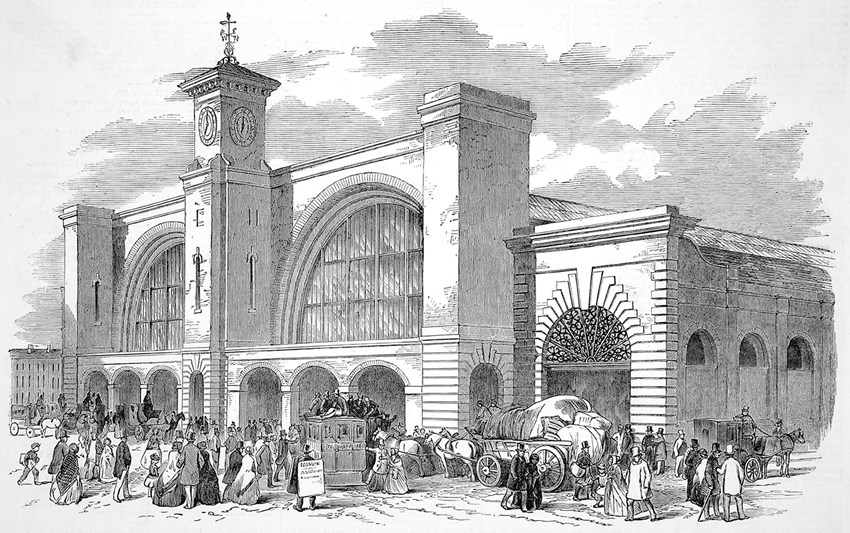

This was followed by the railways with Kings Cross in 1852 and St Pancras in 1868. Housing to accommodate the workers and others newly arrived in London followed with the development of Somers Town and Agar Town. Somers Town attracted international refugees and housed a large population of French Catholics escaping the French Revolution. Agar Town a small estate developed from 1840 to the north and east of Pancras Old Church had a less salubrious reputation due to poor quality housing, no drainage and overcrowding. This reputation was perpetuated by contemporary writers as being a squalid slum housing many poor, drunken Irish. Recent research, studying deeds, Vestry minutes, census and poor law records, suggests this has been exaggerated as it was home to a range of skilled and semi skilled workers associated with local industry such as piano making.

Image: ©Mary Evans Picture Library/ London Illustrated News

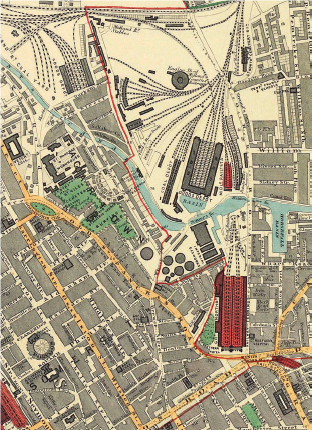

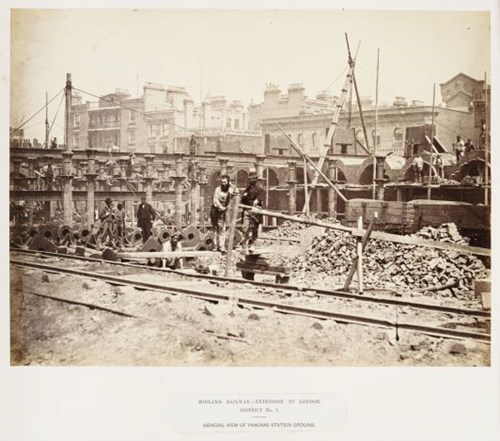

Before the 1860s the Midland Railway Company (MRC) had no direct line into London, routing its traffic via the London and North Western Railway into Euston, and from 1858 via a route into Kings Cross, operated by another rival, the Great Northern Railway. This latter agreement allowed the MRC to build a goods depot on land north of the Regents Canal as the transportation of materials into London was the focus of the railway business. Following disputes in 1862 the Midland Railway put a bill to Parliament for a route from its line at Bedford into a new terminus at St Pancras.

Image: ©Motco Enterprises Ltd

Image: ©Motco Enterprises Ltd

The site chosen by the MRC for its London terminus was unusually complicated. It was constrained on three sides; to the south by Euston Road which demarcated the southern most line at which new rail termini could be built (Metropolitan Railway Commissioners 1846) but which also had the Metropolitan Railway running beneath it; by the Regents Canal to the north; and by the River Fleet to the east. Furthermore the north approach to the site was occupied by a gas works and a burial ground.

Image: ©Mary Evans Picture Library / London Illustrated News

Image: ©Mary Evans Picture Library / London Illustrated News

To make way for the lines and Station large parts of the existing neighborhoods of Somerstown and Agar Town were demolished: 3000 houses in total. Where Agar Town had been falsely portrayed as a foul slum housing a depraved population it fell easy prey to the MRC, who without difficulty obtained Parliamentary powers and in 1868 demolished the area, leaving the inhabitants to find other accommodation wherever they could.

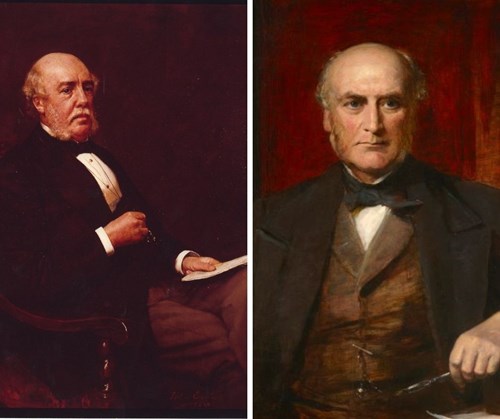

The Midland Railway Company appointed engineers William Henry Barlow (chief engineer) & Rowland Mason Ordish to design the overall station layout, track design and train shed; and George Gilbert Scott, as architect for the hotel and station accommodation which was completed in 1876.

William Henry Barlow (left) ©Institute of Civil Engineers / George Gilbert Scott (right) ©RIBA

William Henry Barlow (left) ©Institute of Civil Engineers / George Gilbert Scott (right) ©RIBA

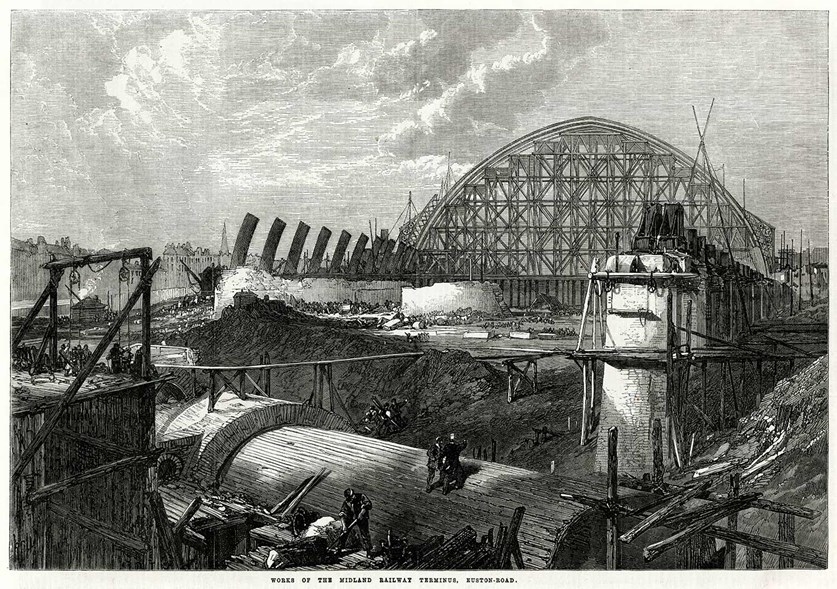

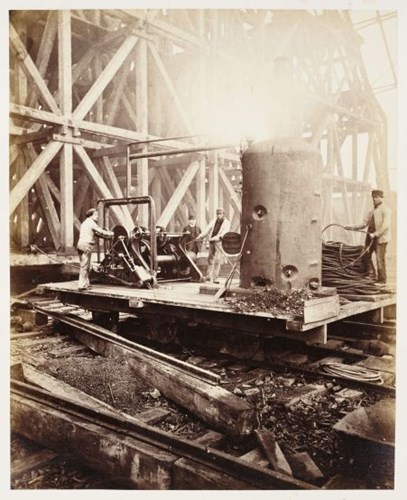

The train station design is a unique response to its site context but also reflects thinking of the day in respect of station design and operation; the platform deck was raised up on a grid of 688 cast-iron columns in order to allow steam engines to pass over the Regent’s canal just to the north and thus avoid the challenging gradient up towards Kentish Town.

Image: ©NRM/ SSPL

The elevation of the platform above street level and the intention to use the resultant space below for commercial purposes, principally beer from Burton on Trent, influenced the design and construction of the track and platform deck. This was constructed of wrought iron girders in a grid of primary and secondary beams; the spaces in between comprising riveted wrought iron plates each slightly convex in section. The deck was supported by 688 cast iron columns. A further advantage to this form of construction was that it formed a ready-made tie sufficient for an arched roof crossing the station in one span, obviating the need for intermediate columns

Image: ©NRM/ SSPL

Image: ©NRM/ SSPL

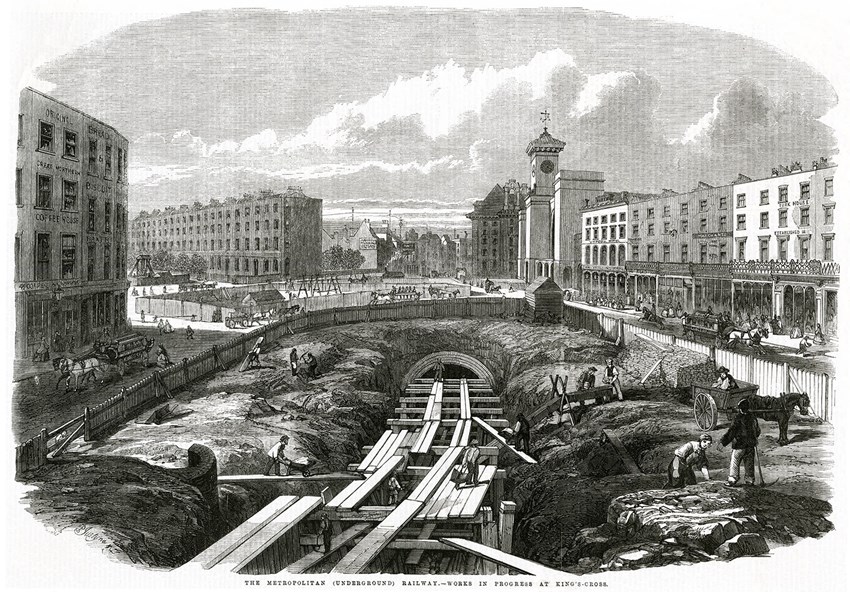

Beneath the undercroft a tunnel was constructed that connected the Midland line into the Metropolitan Railway to the south. This was integral to the foundation to the building and is still in use today as Thameslink

Image: ©Mary Evans Picture Library / London Illustrated News

Image: ©Mary Evans Picture Library / London Illustrated News

The roof is made up of a series of twenty five principal arched trusses, each weighing 55 tons, set at regular intervals and built into massive brick piers. The trusses are linked by longitudinal purlins and rising to a slight point at the crown. This feature differentiates St Pancras from its predecessors which had unbroken rounded arches, and was adopted to afford the greatest possible protection against the lateral action of the wind, although Barlow added that it improved the architectural effect. It was constructed with an enormous timber scaffold on rails, which could move northwards bay-by-bay, each rib taking over a week to assemble. On completion of the station structure the scaffold was dismantled and used for the platform surfaces.

Image: ©NRM/ SSPL

The iron and glass roof was a bold innovation and at the time of its construction was the largest single span roof in the World. It measures 689ft (240m) long, spans 245ft (75m) and is 100ft high (30m).

The materials used to construct the station all originated from the Midlands. From the outset the station was designed to impress and to act as a showcase for the products and skills of the Midlands.

The iron work was manufactured by the Butterley Iron Company which was formed in 1790 as Benjamin Outram & Co to exploit the mineral resources of the Erewash Valley.

A large proportion of the 60 million bricks used to construct St Pancras and its approaches were red facing bricks supplied by Edward Gripper’s Nottingham Patent Brick Company, producers of machine made bricks of consistent quality. When demand outstripped supply additional bricks were supplied by Tucker & Sons of Loughborough. Even the mortar came from the Midlands.

Image: ©Paul Childs

Image: ©Paul Childs

In the undercroft the brickwork was of a more functional utilitarian nature, being continuous arched structures on the east and west walls. These were built of dark multicoloured stock bricks laid in lime mortar with half inch joints. It is likely these bricks were made and fired on site.

Image: ©NRM/ SSPL

Image: ©NRM/ SSPL

The stone used in the original construction also came from the Midlands: Bramley Fell, or Derbyshire gritstone for the foundations; Ancaster & Ketton limestone, Mansfield red sandstone. The limestone beautifully carved into intricate foliate designs.

The head of the trainshed wall was finished with a decorative band of Minton ceramic tiles. The finished station opened on 1st October 1868 and hotel in 1876. Together they form a masterpiece soaring high above its neighbours and beautifully detailed on each elevation. Its rich red brick colour and creamy stone standing out against the traditional yellows and browns of London brickwork.

Image: ©Museum of London

Image: ©Museum of London